Political Interventions

Timeline

1822 – Jean-Pierre Boyer invades Santo Domingo and unifies Hispaniola under Haitian rule

1825 – France sends warships to Haiti and extracts compensation for colonial losses

1844 – Dominican Republic becomes independent from Haiti

1915 – U.S. invades Haiti and occupies it until 1934

1937 – Dominican Republic attacks on Haitian immigrants leave more than 20,000 dead

1947 – Indemnity payments to France finally end

2004 – U.S., Canada, and France send forces to “restore order” after a coup deposed Haiti’s first democratically-elected president

2004-2017 – United Nations Stabilization Mission deployed for peacekeeping

2021 – Assassination of President Jovenel Moïse

2024 – United Nations Peacekeeping Troops Return to Haiti

The Haitian Revolution did not end France’s quest for influence and domination over Haiti. In 1825, France sent warships to Haiti and forced the government to agree to “compensate” former colonists a price of 150 million francs (roughly 3 billion U.S. dollars in today’s currency). This debt contributed to limiting Haiti’s investments in infrastructure and economic development until it was eventually paid off in 1947. By the early 1900s, the United States replaced France as a new force seeking to dominate Haiti economically and politically. In 1915, to protect its economic interests after the assassination of President Guillaume Sam, the U.S. invaded Haiti and occupied the country until 1934.

In 2004, after a coup deposed President Jean-Bertrand Aristide—Haiti’s first democratically elected president—the U.S., Canada, and France sent forces into Haiti purportedly to restore order. From 2004 until 2017, the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) led a controversial peacekeeping mission to maintain the “rule of law.” Currently, Haiti is facing another U.N.-backed occupation after the turmoil following the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, whom the U.S. helped to install to the Haitian presidency in 2017. This long history of international involvement underscores Haiti’s suppression by foreign powers.

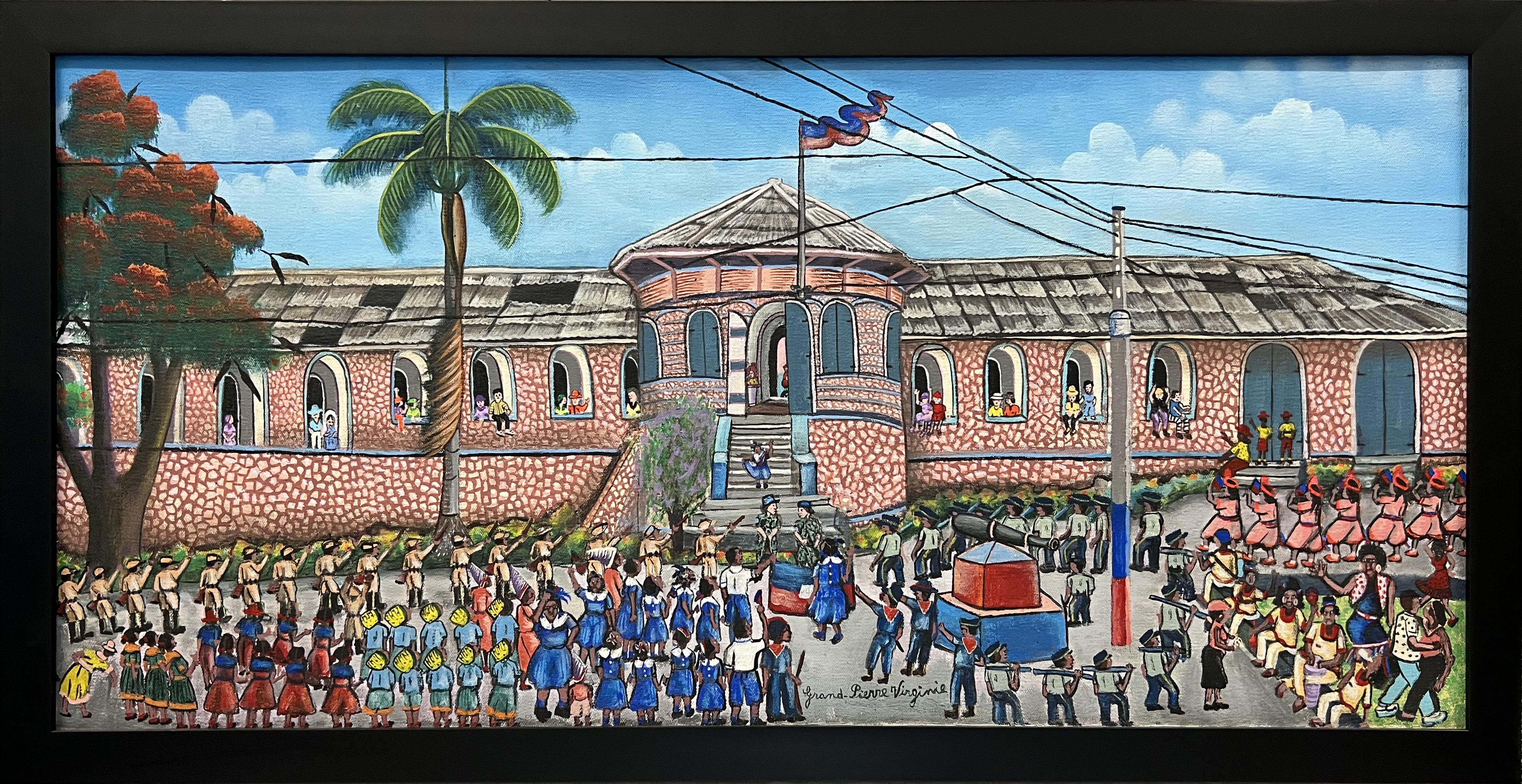

Flag Day (Fèt Drapo) Flag Day (Fèt Drapo)Virginie Grand-Pierre Haiti Friends Collection |

Haiti's Flag Day is observed annually on May 18th. Depicted here in the town of Petite Rivière de l'Artibonite, the gathering of students in their colorful uniforms adds to the festive celebration. The Palace, dating from 1820, was initially intended to serve as a royal residence, reflecting the grandeur and ambitions of Haiti's early post-independence era. The juxtaposition of the youthful celebration against the historic palace creates a powerful image, connecting Haiti's proud past with its hopeful future through the annual tradition of Flag Day.

Transfer of Power (Twansfè pouvwa) Transfer of Power (Twansfè pouvwa) Virginie Grand-Pierre Haiti Friends Collection |

This painting offers a potent critique of political corruption in Haiti and its complex relationship with foreign powers, particularly the United States. By portraying the first Black U.S. president in this scene, the artist underscores the message that despite his African heritage, he continued long-standing U.S. foreign policies that have historically exploited Haiti. Haitian President René Garcia Préval is portrayed as a willing participant in this interaction, highlighting how internal corruption often facilitates external exploitation.

Haiti itself is symbolized by a weakened female figure draped in the national flag, representing the country's vulnerability in the face of these political machinations. The artist does include a hopeful element: an angel (or lwa in Vodou tradition) watching over this transaction. This spiritual presence suggests that despite current hardships, there is divine protection for Haiti, implying that the country will ultimately persevere and overcome these challenges.

The Return of President Aristide in 1994 (Le retour du président Aristide en 1994) The Return of President Aristide in 1994 (Le retour du président Aristide en 1994) Maxan Jean-Louis Haiti Friends Collection |

This painting depicts the controversial return of Jean-Bertrand Aristide to Haiti in 1994, following his forced exile after a 1991 coup. Aristide, often cited as Haiti's first democratically elected leader in the post-Duvalier era, is represented symbolically by a prominent rooster - the emblem of his political party. U.S. Marines, charged with escorting the president back to power, help control crowds of onlooking Haitians. The people's mixture of curiosity and uncertainty is evident, reflecting the complex emotions surrounding Aristide's return to a nation grappling with its future after decades of dictatorship.

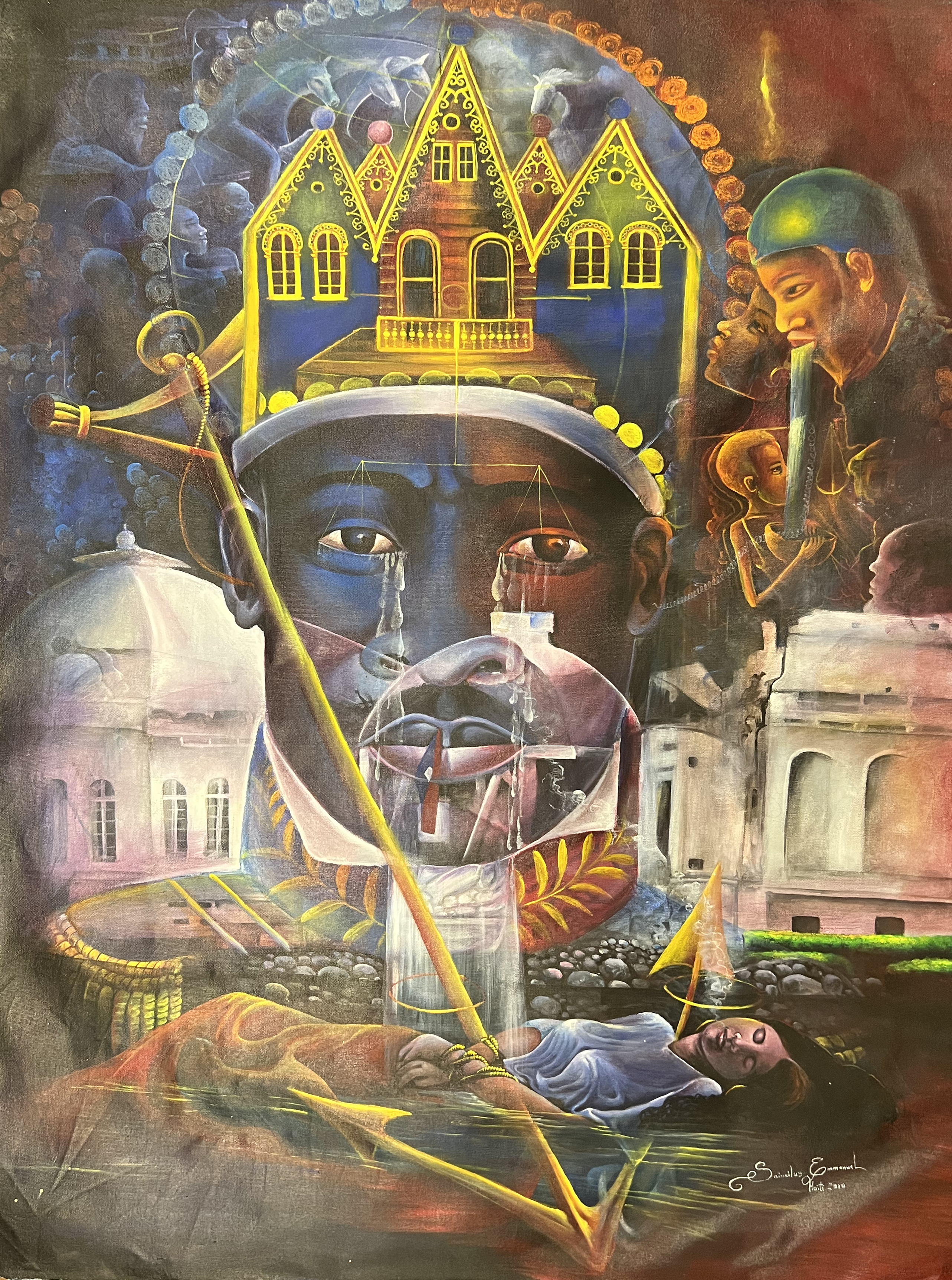

Jean Jacques Dessalines’ Response to Haiti’s 2010 Earthquake Jean Jacques Dessalines’ Response to Haiti’s 2010 Earthquake Emmanuel Saincilus Haiti Friends Collection |

Jean Jacques Dessalines, the leader of the Haitian Revolution of 1803, is poignantly depicted experiencing profound sadness in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. The devastation caused by the earthquake left the country in ruins and vulnerable to foreign forces who exploited Haiti for financial gain. Dessalines, with a heavy heart, is asking for justice for the country and its people who continue to face unimaginable hardships. His expression reflects the pain of a nation seeking solace and restoration.

Haiti itself is symbolized by a weakened female figure draped in the national flag, representing the country's vulnerability in the face of these political machinations. The artist does include a hopeful element: an angel (or loa in Vodou tradition) watching over this transaction. This spiritual presence suggests that despite current hardships, there is divine protection for Haiti, implying that the country will ultimately persevere and overcome these challenges.

Haiti and the Dominican Republic

Relations between Haiti and the Dominican Republic have long been contentious. Following Haiti’s independence, revolutionary leader Jean-Pierre Boyer invaded eastern neighbor Santo Domingo in 1822 and unified the island of Hispaniola under a single government. It was not until 1844 that Santo Domingo declared its independence from Haiti. The cultural, economic, and political differences have led to many dark periods between the two countries. In 1937, in what became known as the Parsley Massacre (Kout Kouto-a), the dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the expulsion or killing of Haitians living and working in the Dominican Republic, with more than 20,000 Haitians killed in the ensuing massacre. Tensions continue to this day with the current Dominican Republic president Luis Abinader seeking to control Haitian immigration. His plans include building a 106-mile-long wall between the two countries.